Every breath is a chance to reborn spiritually.

But to be reborn into a new life,

you have to die before dying.

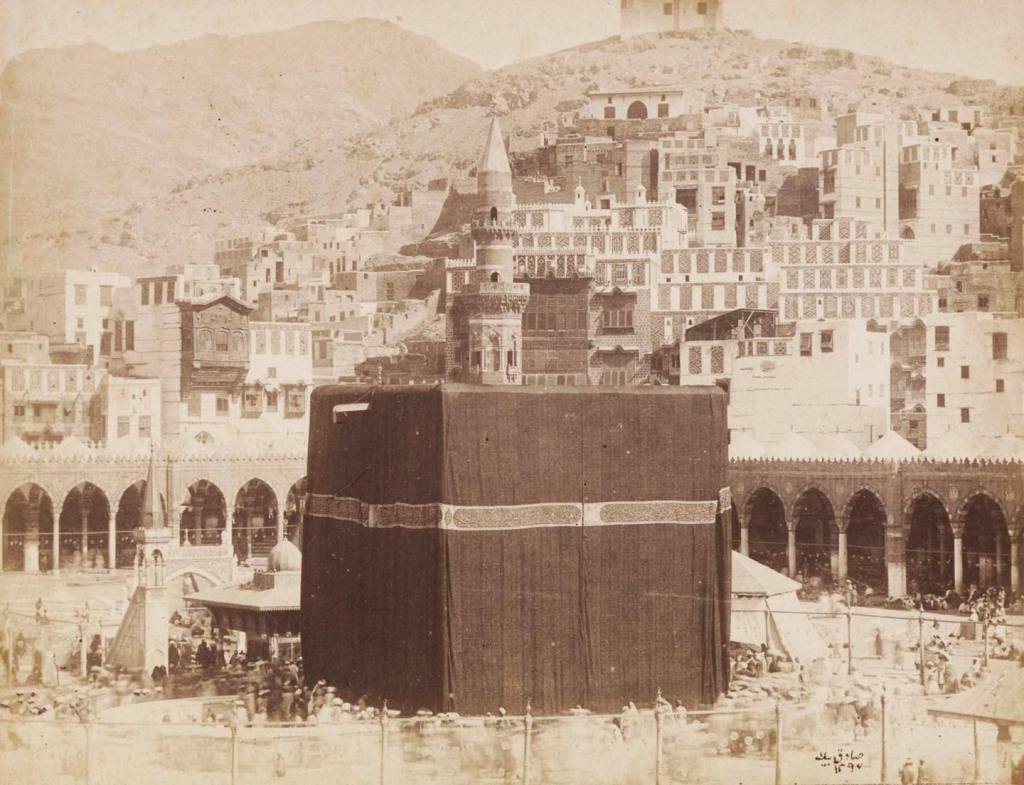

*THE KA’ABA* by HAJJAH AMINA ADIL (RA)

Bismillah Hir Rahman Nir Raheem

S. Ibrahim (as) was ordered to rebuild the Ka’aba, which had been hidden in the earth after the flood of Nuh (as). At the time of the flood, Mount Qubays (a mountain outside of Mecca) asked Allah, “Let me hide your amanat. ” So Allah placed the black stone safely inside the mountain. Then Allah put a little hill over the spot on which the Ka’aba had stood to mark it.

Ibrahim (as) asked his Lord, “Where and how should I build it?” Jibrail (as) came and removed the hill with his wing. Then a cloud appeared and shaded the area of the sanctuary so that its boundaries were made clear.

Then Mount Qubays asked Allah that the Ka’aba be built from its stones. This Ibrahim (as) and Ismail (as) did and mixed the mortar with zamzam water.

The order came from Allah. Jibrail (as) was the architect. Ibrahim (as) was the mason and Ismail (as) was the labourer.

Ibrahim (as) built the walls as high as he could reach. Then he took one large stone to stand on so that he could build higher. As the building grew the stone increased in height and it moved around the Ka’aba on its own with Ibrahim (as) standing on top of it. After the Ka’aba was completed this stone stayed nearby and became what we now know as Maqam Ibrahim (as).

Then Hajjar (ra), Sara (ra), Ismail (as), and Ishaq (as) came to make tawwaf. S. Ibrahim (as) was tired and he sat down. He was exhausted but he wanted to clean the area before making tawwaf. Just then a big wind blew through and carried all the debris and dust and dirt away. Those small bits of rock were distributed by the wind all over the world. Wherever a stone fell a mosque was or will be built until the end of time.

The Ka’aba is called Bayt Allah, the House of God, because all people are welcome there.

S. Ibrahim (as) made du’a that out of his love for the community of the coming Prophet Muhammad (sas) he could make shafa’a, intercession, for all the old people who would journey to the House. S. Ismail (as) asked for shafa’a for all the middle-aged people. S. Ishaq (as) asked for shafa’a for all the young people. S. Sara (ra) asked for shafa’a for all the women, and S. Hajjar (ra) for all the slaves and servants, both men and woman.

Then Ibrahim (as) put up his hand and said, “We love the community of the Prophet Muhammad (sas) and the pilgrims who will come will love him. They will only pray for their Prophet (sas) and they will forget all about us. ”

Allah answered that He would make it obligatory in the five prayers to remember Ibrahim (as) and his family. Ibrahim (as) was very satisfied with this promise.

After making Hajj, Ibrahim (as) left Hajjar (ra) and Ismail (as) and returned to the mountains on the border of Arabia and Palestine. One side of the mountains is green and one side brown and dry. There he prayed, “O my Lord, I left some of my family in a distant desert valley (Mecca) so You make people come to them. ” And today whatever you might want you will be able to find in Mecca..

Then Allah ordered Ibrahim (as) to call the people to come for pilgrimage, Hajj. S. Ibrahim (as) asked, “But my Lord who will hear me?” Allah ordered him, “Call and they will hear. ” So Ibrahim (as) raised his voice and began calling the people. When he finished he started to hear voices from far away like the buzzing of bees. “Labbayk Allahuma Labbayk” cried the voices.

“O Allah, ” Ibrahim (as) cried, “All those people are coming. How will I host them?” S. Jibrail (as) came down with a glass of water. He told Ibrahim (as) to throw this water into the wind. The wind took the drops of water all over the world. Wherever they landed they became salt. On the mountains they became rock salt. On the sea they became sea salt. Whoever uses this salt is enjoying the hospitality of S. Ibrahim (as) until the end of time.

The souls who answered Labbayk once will make Hajj one time. The souls who answered twice will make Hajj two times and so on.

The first Ka’aba was actually the Bayt al Ma’mur which, at the time of the flood, was raised to the fourth heaven. It is there today and the angels make Tawwaf around it. It is exactly the same as the Ka’aba in Mecca and directly above it. If it should fall it would occupy exactly the same space. But it will not fall or come to this earth again.

Al Fatiha

HAJJAH AMINA ADIL (RA)

The Feast of Sacrifice

Mawlānā retells the story of the Pied Piper but with a beautiful ending. In such a way, Allāh gives the Awliyā’ a divine music that no one can resist.

The Pied Piper of Hamelin (German: Rattenfänger von Hameln, also known as the Pan Piper or the Rat-Catcher of Hamelin) is the titular character of a legend from the town of Hamelin (Hameln), Lower Saxony, Germany. The legend dates back to the Middle Ages, the earliest references describing a piper, dressed in multicolored (“pied”) clothing, who was a rat-catcher hired by the town to lure rats away[1] with his magic pipe. When the citizens refuse to pay for this service, he retaliates by using his instrument’s magical power on their children, leading them away as he had the rats. This version of the story spread as folklore and has appeared in the writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Brothers Grimm, and Robert Browning, among others.

The Pied Piper of Hamelin: The rats/mices that infest the town are symbolic of all the sins, corruption and false beliefs that plague the people. The Pied Piper is a man who comes to show the people the path to the light. He asks for a vast reward since he knows that this is the supreme test of the townspeople. If they have listened to his message, they will have no more need of their gold because they will have lost their materialistic greed and they will no longer worship money. They will be happy to pay him the agreed sum (symbolising that they have progressed from the materialistic to the spiritual plane). The Piper succeeds in driving out the rats (the moral pollution) from the community, but it is a short-term success. When the time comes for the townspeople to pay the Piper, they are still wedded to their old greed and materialism and they don’t give him his due. The Pied Piper realises that these adults are incapable of changing their wicked ways, so he leads the children to salvation instead, ensuring that they are cut off forever from the malignant influence of the adults. This is symbolised by the magic mountain opening (the Koppenberg Mountain), the children going inside and then vanishing forever from the knowledge of the townspeople. The only child who fails to gain admission to paradise is the crippled boy (symbolising that he has been too badly injured by the beliefs and corruption of the townspeople to take the decisive step to Knowledge).

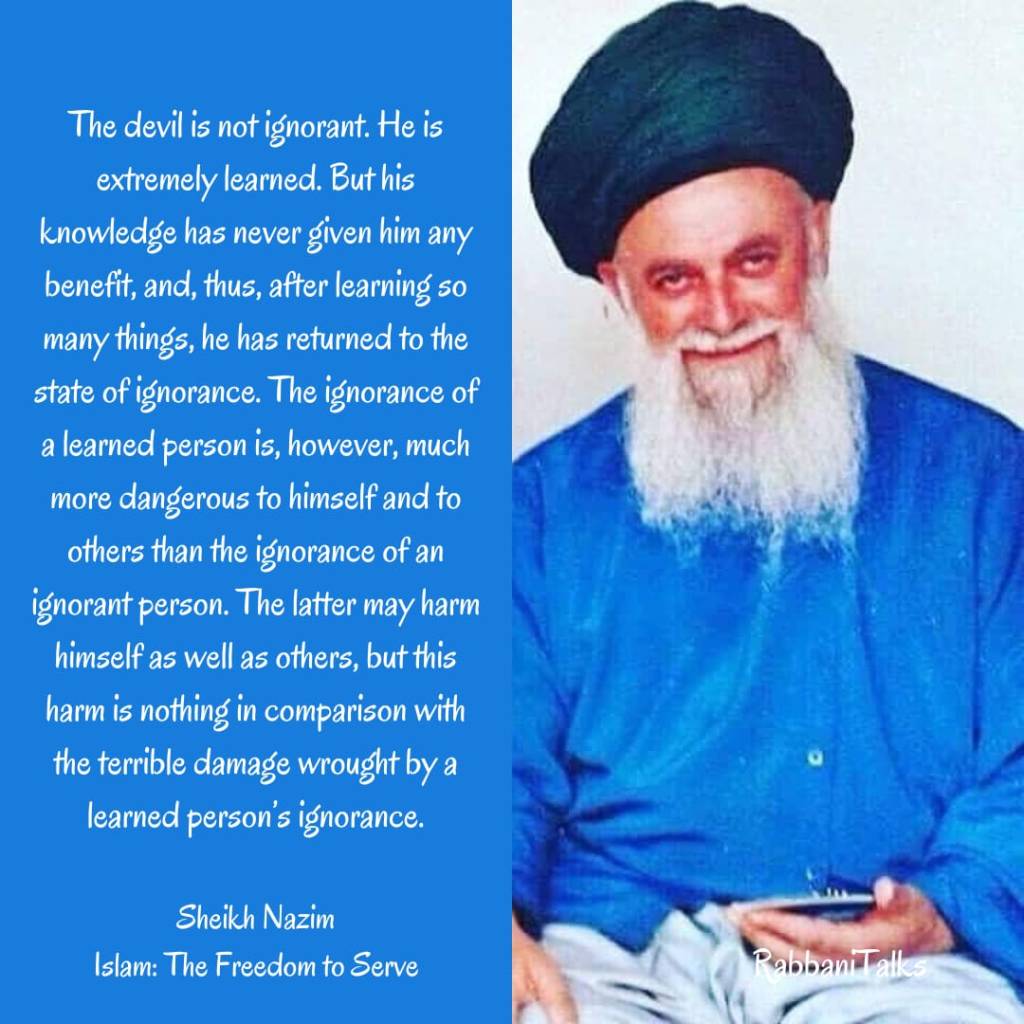

Read here : Islam, the freedom to serve

«We ask to be no-one and nothing,

For, as long as we are someone,

we are not complete.»

Art of Islam, Language and Meaning: Commemorative Edition, By

Titus Burckhardt, Foreword by Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Introduction

by Jean-Louis Michon, Translated by J. Peter Hobson, Bloomington.

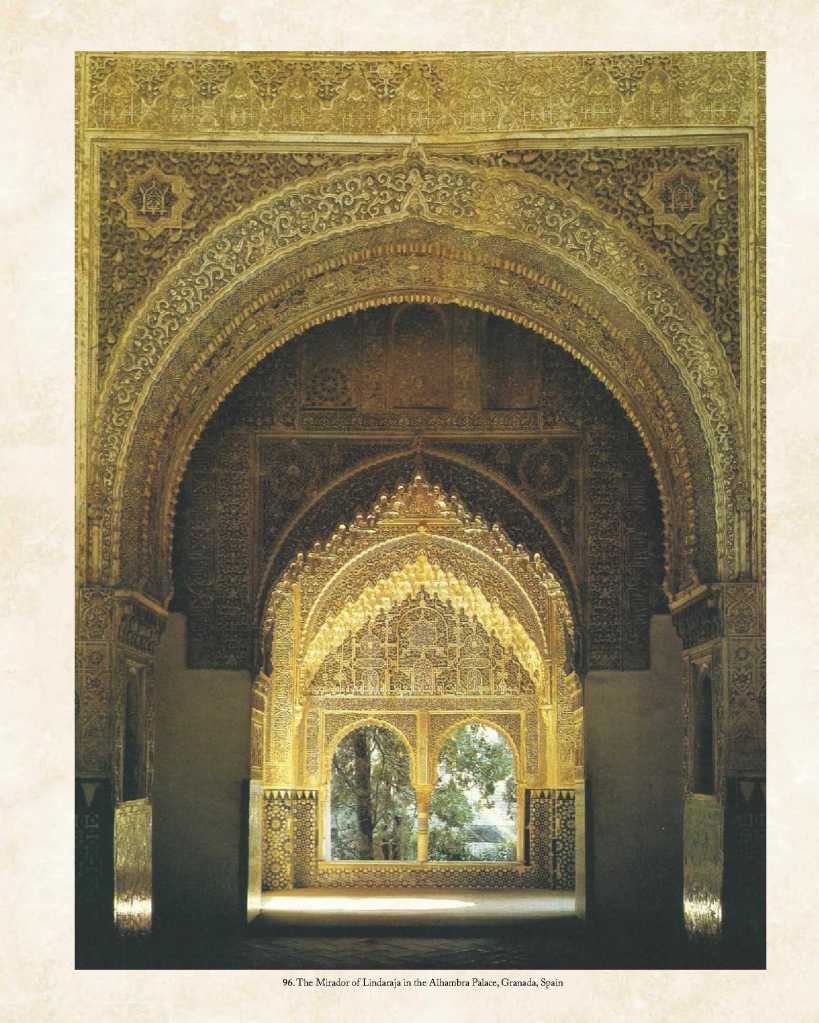

Art of Islam is a masterpiece and is considered to be the most in-depth study on the subject ever written. It was commissioned by the World of Islam Festival (London) and originally published in 1976; in 2009 it was republished in a revised commemorative edition featuring over three hundred fifty color and black-and- white illustrations (two hundred eighty-five of which are new), and including a new introduction.

Titus Burckhardt (1908–1984) was one of the most widely respected authorities on Islamic art as well as having a profound understanding of the Islamic tradition and its mystical dimension, Sufism.

In his foreword, the world-renowned Islamic philosopher, Seyyed Hossein Nasr (b. 1933) has called this classic book “the definitive work on Islamic art as far as the meaning and spiritual significance of this art are concerned” (p. viii). Elsewhere he has written that Burckhardt “had been the first person in the West to expound seriously the inner meaning of Islamic art.”

This work is organized into eight chapters:

(1) Prologue: The Ka‘ba; (2) The Birth of Islamic Art; (3) The Question of Images; (4) The Common Language of Islamic Art; (5) Art and Liturgy; (6) The Art of Sedentaries and Nomadic Art; (7) Synthesis; and (8) The City.

This volume brings the wide spectrum of art within the Islamic tradition to broader audiences. It also provides the spiritual keys to discern these forms and to connect them to the metaphysical principles of the Islamic revelation, which is to see that its art forms are the earthly crystallization of Islam itself. To ask the question “What is Islam?” it would suffice to point to one of its remarkable art forms such as the Mosque of Córdoba, Ibn Tulun in Cairo, one of the madrasahs in Samarqand or the Taj Mahal. Hence what is considered to be the most outward manifestation of religion or civilization, such as art, correspondingly reflects its most inward dimension of that civilization.

In Islam, the outward is known as az- zahir and the inward as al-batin, a perspective that views God as both transcendent and immanent, both of which are joined in the Divine Unity (tawhid). The birth of all sacred art, in fact, is associated with the exteriorization of that which is most

inward in every sapiential tradition; therefore, there is an important connection between art and the mystical dimensions of all religions.

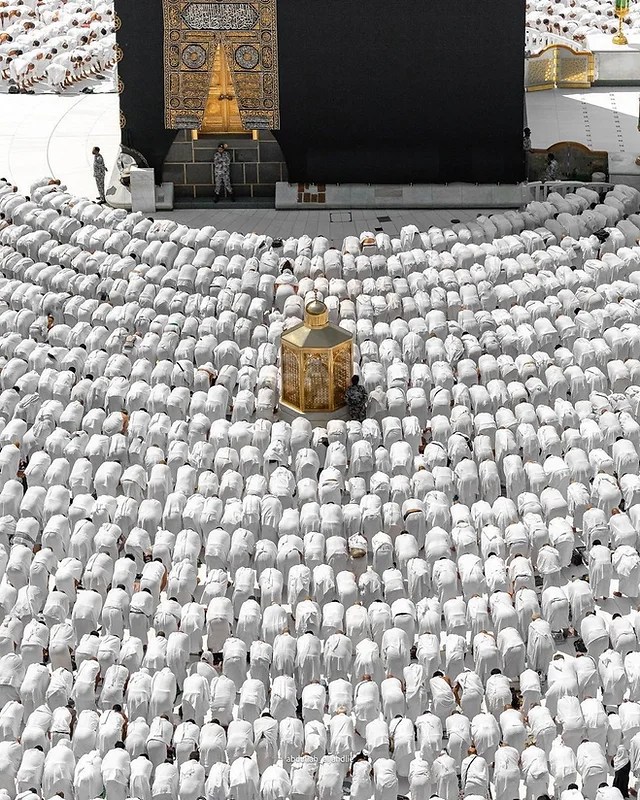

The Ka‘ba, as the liturgical center of the Muslim world, is inextricably linked to the origin of the Abrahamic monotheisms—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—and demonstrates Islam’s connection to all the monotheist religions. The notion of center and origin are presiding ideas, as they are “two aspects of one and the same spiritual reality, or again, one could say, the two fundamental options of every spirituality” (p. 1). The Koran explains that “Abraham was neither Jew nor Christian, but detached (hanif) and submitting (muslim)…” (3:67). Abraham was the apostle of pure and universal monotheism, which the Islamic tradition purposes to renew. The Ka‘ba, although not a work of art as such, can be regarded as “proto-art” whose metaphysical dimension is linked to myth and revelation, therefore containing the embryo of the whole of Islamic art.

According to Burckhardt “The art of Islam … is abstract, and its forms are not derived directly from the Koran or from the sayings of the Prophet; they are seemingly without scriptural foundation, while undeniably possessing a profoundly Islamic character” (p. 7). He adds that “Art never creates ex nihilo. Its originality lies in the synthesis of pre-existing elements” (p. 18).

The prohibition of images in Islam is specifically associated with images of the Divine. As Islam is the renewal of Abrahamic monotheism, the Prophet Muhammad, as Abraham before him, opposes idolatrous polytheism. To produce images of the Divine is to perpetuate the error that associates the relative with the Absolute or the created with the Uncreated, reducing one level to another. The term aniconism is used to depict the art of Islam, which differs from iconoclasm. Burckhardt elaborates:

As for Islamic aniconism, two aspects in all are involved. On the one hand, it safeguards the primordial dignity of man, whose form, made “in the image of God”, shall be neither imitated nor usurped by a work of art that is necessarily limited and one-sided; on the other hand, nothing capable of becoming an “idol”, if only in a relative and quite provisional manner, must interpose between man and theinvisible presence of God. What utterly outweighs everything else is the testimony that there is “no divinity save God”; this melts away every objectivization of the Divine before it is even able to come forth. (p. 32)

The immutable essences (al-a’yan ath-thabitah) of things, their archetypes, are not apprehended, as they are beyond form; however, they are reflected in the contemplative imagination of the believer. Everything that exists in the cosmic order, exists in this hierarchy, which manifests qualitatively and not quantitatively.

Burckhardt states:

The most profound link between Islamic art and the Koran … lies not in the form of the Koran but in its haqiqah, its formless essence, and more particularly in the notion of tawhid, unity or union, with its contemplative implications; Islamic art … is essentially the projection into the visual order of certain aspects or dimensions of Divine Unity. (p. 51)

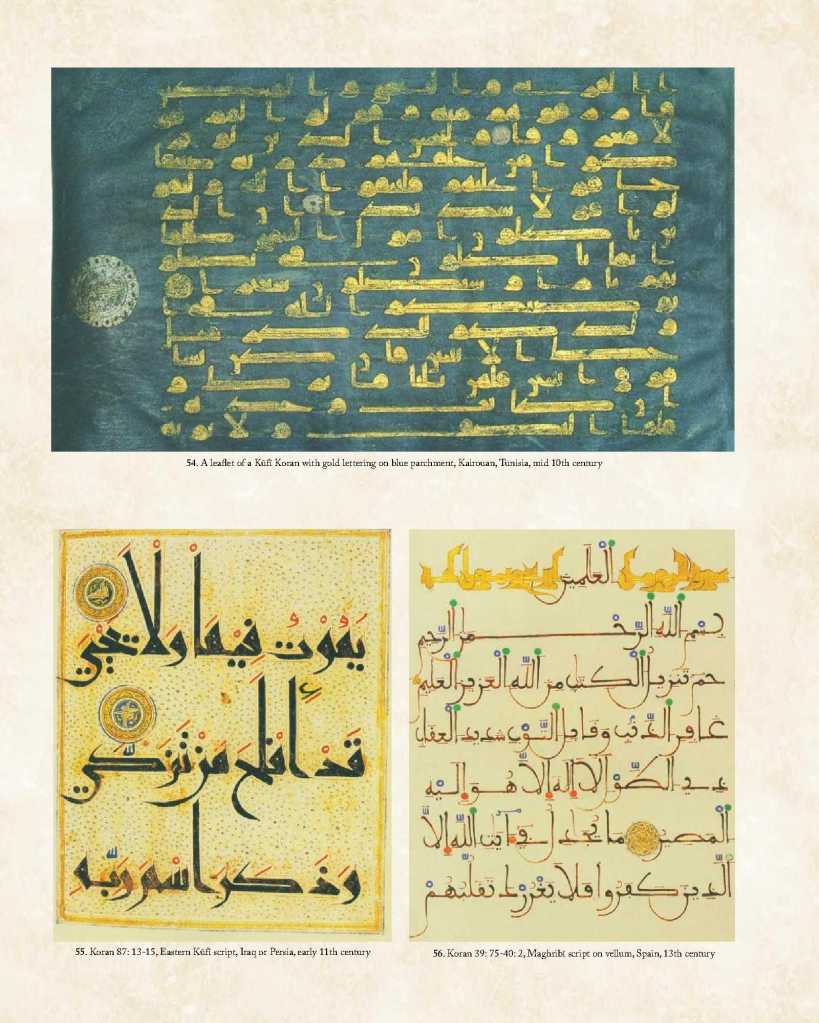

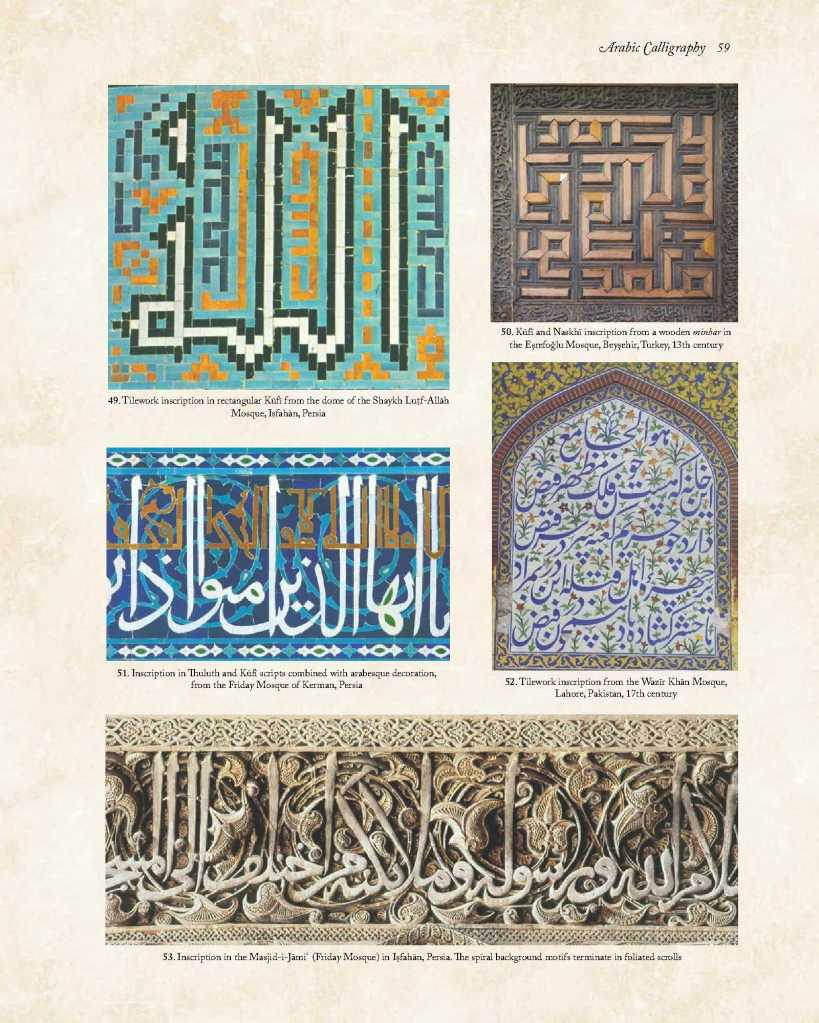

Calligraphy is a widely used art form among Muslims. In weaving the horizontal and vertical movement of the script, change and becoming are juxtaposed with what is immutable. Burckhardt adds, “The vertical is therefore seen to unite in the sense that it affirms the one and only Essence, and the horizontal divides in the sense that it spreads out into multiplicity” (p. 54).

As human diversity is inexhaustible, so is the cosmic order, all of which is contained in the Divine Unity. It is reflected through harmony, which is expressed as “unity in multiplicity” (al-wahdah fi’l-kathrah) and “multiplicity in unity” (al- kathrah fi’l-wahdah). This interpenetration is the expression of one abiding in the other, yet all things ultimately return to the Divine Unity. Again, “Islam is the religion of return to the beginning, and … this return shows itself as a restoration of

all things to unity” (p. 66).

The central theme of the Islamic tradition is Divine Unity, which exists a priori everywhere and always. The decisive task for the human being is to realize the Divine Unity in him or herself and the cosmic order.

Worship is inseparable from beauty, as the hadith instructs: “God has inscribed beauty upon all things.” Hence, “Sacred art … fulfills two mutually complementary functions: it radiates the beauty of the rite and, at the same time, protects it.” (p. 88)

From this perspective, a rite itself is sacred art. A pulpit, known in Arabic as a minbar, symbolizes the ladder of the worlds—these are the corporeal, the psychic, and the spiritual.

Note: SALAH AL-DIN MINBAR OF AL-AQSA MOSQUE

Salah Al-Din Minbar (pulpit) has a distinguished value in Islamic art, which is originated from its historical value of being constructed 800 years ago epresenting a symbol of dignified historical era; and to its political

value as this Minbar had formed an emotional spur during the Crusades; and above all it is considered as one of the most beautiful and finest pieces of Islamic decoration art. Read Here

There is a liturgical and artistic role of clothing in Islam. Burckhardt clarifies, “To veil the body is not to deny it, but to withdraw it like gold, into the domain of things concealed from the eyes of the crowd” (p. 105).

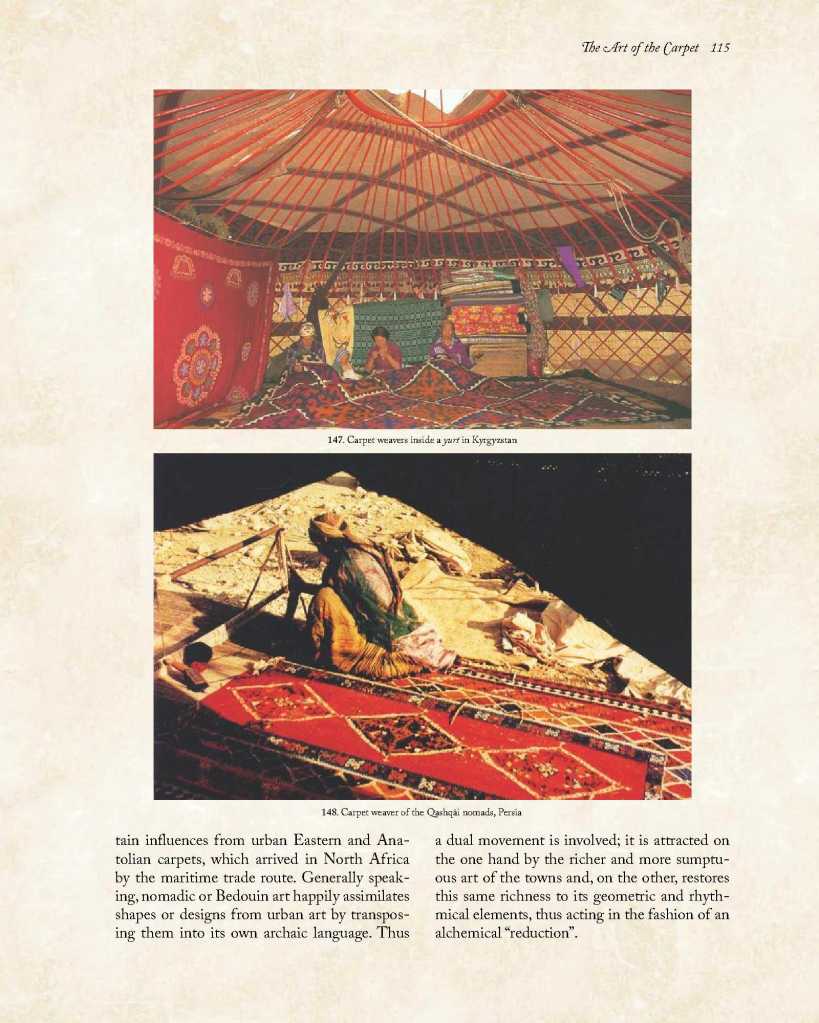

The significance of the carpet within Islamic spirituality is illuminated here, It is the image of a state of existence or simply of existence as such; all forms or happenings are woven into it and appear unified in one and the same continuity. Meanwhile, what really unifies the carpet, namely the warp, appears only on the borders. The threads of the warp are like the Divine Qualities underlying all existence; to pull them out from the carpet would mean the dissolution of all its forms. (p. 119)

Burckhardt maintains that art should be “typified by beauty” and dismisses contemporary discussions of functions by stating that “certain functions owe their existence to man’s decadence” (p. 156). He adds, “The only beautiful work of art is the one which, in some way, reflects integral human nature whatever its incidental function” (p. 156). There is an important awareness of the ephemerality of all things in the cosmic order; for this reason, art always includes something provisional pertaining to it—“We shall surely make all that is upon it [the earth] barren dust” (Koran 18:8).

Burckhardt’s work has stood the test of time and has demonstrated its enduring value to those wanting to understand the art of Islam. Because modern art has no parallels with Islamic art, or any sacred art, for that matter, it challenges the Western mindset and its Eurocentrism—its ability to appreciate art as understood in a theocentric civilization, where nothing stands outside the sacred. Art in this context contains something beyond its artistic form, something timeless and universal, as there is no “art for art’s sake” in Islam or any other sacred art. The important connection between sacred art and contemplation has been forgotten and lost in the modern world. The Prophet defines ihsan as “serving [or worshiping] God as if you see Him, because if you do not see Him, He nonetheless sees you.” It is in tracing beauty, whether in a form of art or in the cosmic order, back to the origin that we can realize that the metaphysical dimensions of aesthetics are a doorway to the Divine. As the Prophet has expressed it, “God is beautiful and He loves beauty” (p. 224).